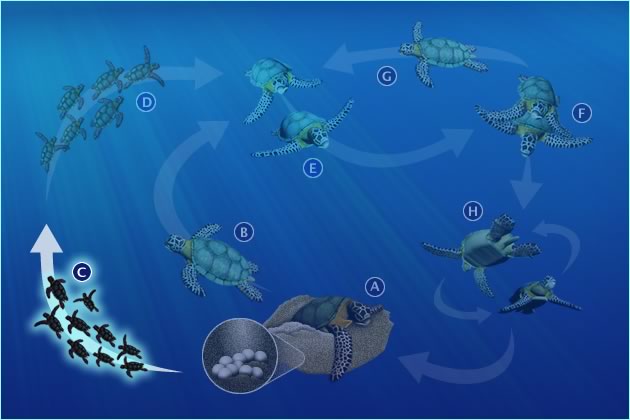

Sea Turtle Life Cycle

The life of a sea turtle begins on the beach, when a hatchling turtle emerges from its egg and crawls quickly into the ocean, where they will spend most or all of the rest of their life. On this page, we explore the sea turtle life cycle in depth, from egg to hatchling to adult.

Watch: Sea Turtle Life Cycle Video

For a quick overview of the life cycle of sea turtles, watch our short video about sea turtles below. To explore in depth, read through our detailed description of the sea turtle life cycle and explore our interactive diagram below.

Discover: Life Cycle of a Sea Turtle in Detail

Sea turtles spend most of their lives in the open ocean, migrating between their foraging (feeding) grounds and nesting beaches, mating, and searching for food. Below we dive into the intriguing life cycle of sea turtles, from hatchling to adult.

A. NESTING BEACHES: ADULT FEMALES

A green turtle returns to the ocean after laying a clutch of eggs. She will return to this beach to lay more clutches before migrating back to her feeding grounds to replenish her fat stores before returning to nest on the same beach a couple years later.

During nesting season, female sea turtles come ashore to lay eggs within a few weeks of mating.

After crawling out of the ocean and making their way above the high-tide line, they use their front flippers to dig a large depression called a “body pit,” using such force that they send sand flying through the air.

Females then use their rear flippers to dig a smaller hole at the far end of the body pit called an “egg chamber,” into which they deposit between 50-200 soft-shelled eggs, depending on the sea turtle species. After covering their egg chambers with sand, they spend some time camouflaging their nest before returning to sea. They will then wait offshore for about one week before hauling ashore again to lay another clutch of eggs. Depending on the species, female sea turtles will repeat this process between 2 and 7 times during one nesting season.

B. ADULT FEMALE sea turtles RETURN TO FEEDING AREAS AFTER NESTING SEASON

After nesting, adult female sea turtles migrate back to their feeding areas. Depending on the distance, this migration may take several months.

Female turtles must return to feeding areas – generally nearshore (neritic) areas – after each nesting season to replenish their energy stores before they are able to reproduce again. This typically takes more than a year, and in many cases, several years, depending on the availability of food and other factors. Other adults (females and males) and large juveniles also feed in these areas.

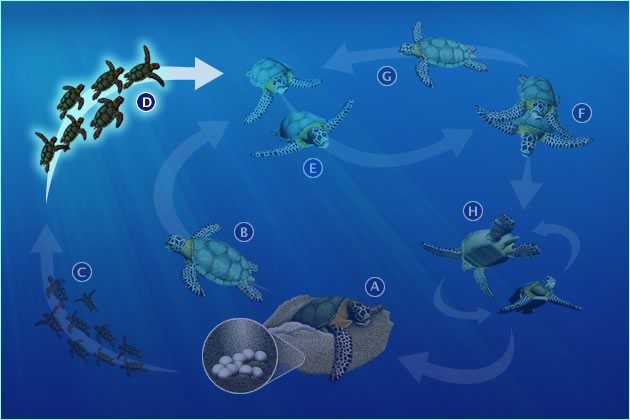

C. Sea Turtle HATCHLINGS Emerge aND spend EARLY YEARS IN OPEN OCEAN HABITAT

Emerging from the nest is a collaborative effort for sea turtle hatchlings. They work together, coordinating small movements that slowly moves them as a group up the nest column to the surface. Once they reach the surface, like these newly hatched olive ridley turtles, they will all crawl as quickly as possible to the ocean.

After the eggs have incubated in the sand for 45-65 days (depending on the species and the sand temperature), sea turtle embryos will be fully developed. At this point, hatchlings “pip,” using a temporary egg tooth on their beak to break through their eggshell. Over multiple days, they will slowly dig their way to the surface, with all (or almost all) of the hatchlings from a nest emerging at the same time.

Hatchlings generally wait until night to emerge from the sand and head for the ocean, so that they can use the cover of darkness to avoid detection by some predators, like birds. Scientists believe that the nighttime drop in temperature is a cue for the hatchlings to leave the nest and head to the ocean.

At this point, hatchlings enter into a multi-day “frenzy state" during which they swim almost continuously, fueled only by leftover egg yolk, to reach deeper water away from shore. They are very vulnerable to predation at this stage of life.

Little sea turtles are transported by strong ocean currents to open-ocean (oceanic) habitats, where they live in flotsam, such as Sargassum mats (brown algae), and have an omnivorous diet. This oceanic stage can last from a few years to decades.

Leatherbacks are the only species that spend the majority of their life in this oceanic environment; flatbacks are the only species that lack this open ocean stage entirely.

>> Read More: Where do Baby Sea Turtles Go When They Hatch?

D. Juvenile sea turtles migrate TO Near shore (NERITIC) FEEDING AREAS

After this oceanic period, juvenile sea turtles move into highly productive neritic (near shore) feeding areas to finish growing, a process that can take as little as a few years and as long as a few decades!

These foraging (feeding) grounds tend to offer a greater abundance and variety of food than the open ocean, but they also tend to host more predators. That is why young turtles wait to enter these areas until they have reached a larger body size, helping them to avoid being eaten.

Adult turtles also occupy neritic feeding areas. Adult turtles remain in these areas until they have accumulated sufficient energy reserves to migrate to breeding areas for reproduction. This period typically takes more than a year, and in many cases, several years.

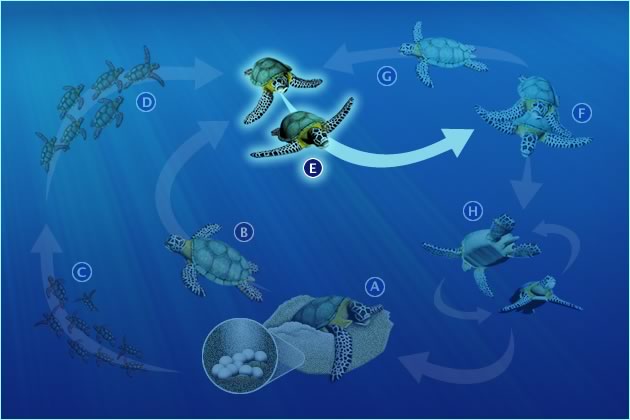

E. Adult sea turtles migrate to natal beaches to mate

After acquiring sufficient fat stores, adult male and female sea turtles migrate to breeding areas to mate and, in the case of females, to nest.

The distance between feeding and breeding areas can be hundreds, to tens of thousands, of kilometers.

Each nesting season, most female sea turtles return to nest at the same beach, or group of beaches, from which they were born. The return migration by an adult turtle to the beach of its birth is called natal homing.

F. Sea turtles MATe IN COASTAL AREAS NEAR NESTING BEACHES

This female green turtle (center) is surrounded by interested male sea turtles who compete with one another to mate with her. They will also bite the mounted male in an attempt to dislodge him and take his spot. © Tui de Roy / Roving Tortoise Photos

Although a female turtle only needs to mate with one male to obtain enough sperm to fertilize all of her eggs in a season, multiple paternity is common in sea turtles. This is most likely due to the fact that male sea turtles generally attempt to mate with as many females as possible. Scientists have found that one nest may contain hatchlings from multiple males!

Males are quite aggressive during the mating season, both with other males and with females.

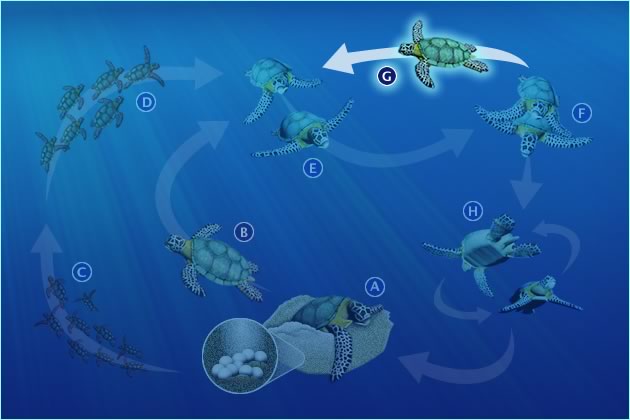

G. ADULT MALES RETURN TO FEEDING AREAS

Like females, male turtles show natal homing, but visit broader areas and more sites than females do. Males will try to mate with as many females as they can during a season. Once males have mated and are unsuccessful in finding more mates, they return to their feeding areas.

H. INTERNESTING HABITATS

Females stay near their nesting beach during the nesting season, which can last one to two months.

Depending on the species, female turtles lay between two and seven clutches (a group of eggs deposited during one egg-laying event), in a season – one clutch every 7 to 15 days.

Olive ridley and Kemp’s ridley turtles are the exceptions to this pattern when they nest in arribadas, or synchronized mass nesting events, that occur over a three to seven-day period once a month.

Explore: Sea Turtle Life Cycle Diagram

Learn about the sea turtle life cycle through our interactive diagram. Click through the images to see the different phases in a sea turtle’s life cycle, and read the detailed description of each stage of the cycle below.