Sea Turtles: The Ultimate Expert Guide

Sea turtles have survived on Earth for more than 100 million years, yet today their future hangs in the balance. In this comprehensive, expert-written guide, we cover everything you need to know about sea turtles. Most importantly, you’ll also learn all about sea turtle conservation issues and how you can help save sea turtles. From fun facts to the latest science, conservation issues, and frequently asked questions, we’ve got you covered!

© Amanda Cotton / Ocean Image Bank

To help you find what you’re looking for, here is a complete list of topics that we cover on this page. In each section, you’ll find links to reputable content for further reading.

Jump to topics covered on this page:

This page is updated regularly with new information. Let us know if we missed anything!

Sea Turtles 101 Video

Curious about sea turtles, their life cycles, and conservation? Watch this short video for an introduction to the key facts covered in this guide.

Sea Turtle Species

There are seven species of sea turtles found worldwide today. Six of them are hardshell species belonging to the family Cheloniidae:

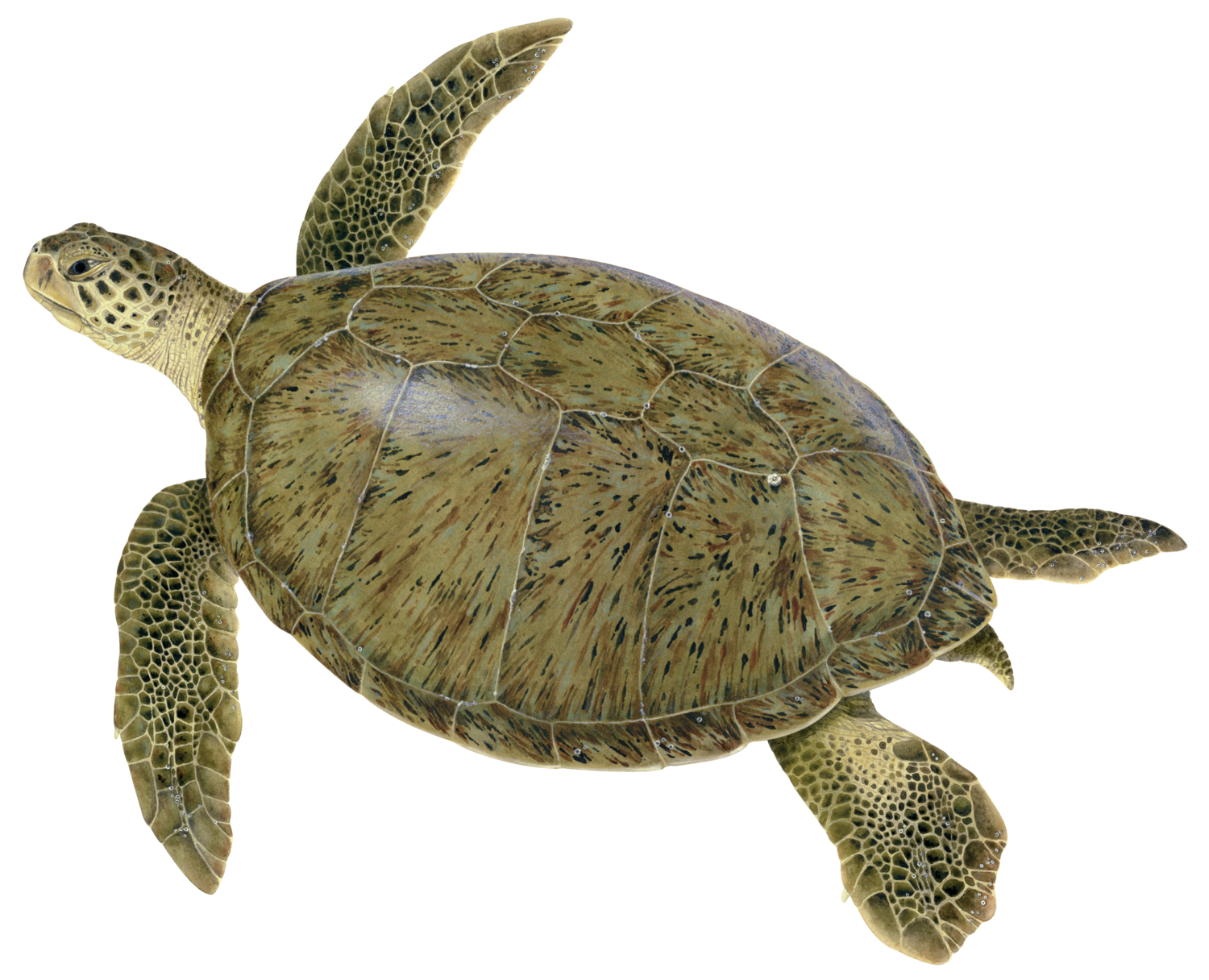

© Dawn Witherington

Green turtle (Chelonia mydas)

Perhaps the most iconic sea turtle species (e.g. Crush in Finding Nemo), the green turtle also has the most numerous and widespread nesting sites of the seven species. Green turtles are found throughout the tropical and subtropical regions of the world and in all major ocean basins. They are often found among coral reefs and in other shallow water habitats, including among seagrasses, which are a key component of their diet. Green turtles are also found basking on beaches in Hawaii (where they are known as honu), and in a few other locations like the Galápagos Islands. Green turtles were once extensively hunted for their body fat, a key ingredient in the once popular delicacy ‘turtle soup.’ Although it has become illegal to hunt sea turtles in most parts of the world, green turtles and their eggs continue to be consumed. Learn more about green sea turtles.

Loggerhead turtle (Caretta caretta)

Loggerhead turtles are named for their large heads, with jaws powerful enough to crush an adult queen conch and other mollusks and crustaceans that make up a key component of their diet. Like some other sea turtle species, loggerheads are famed for their vast migrations. They are found worldwide, with major nesting areas in the southeast U.S., Brazil, the Mediterranean Sea, Cabo Verde, South Africa, the Middle East, Japan, and Australia. As a species that may travel thousands of miles across ocean basins, loggerheads are exposed to a wide range of threats including pollution, habitat loss, and incidental capture by fishermen. Learn more about loggerhead sea turtles.

© Dawn Witherington

© Dawn Witherington

Hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata)

Named for their sharp, pointed beaks, hawksbill turtles feed primarily on reef sponges as adults. The bodies of these invertebrate organisms contain tiny indigestible glass needles, making hawksbills one of their only predators. The hawksbill has a beautiful shell that has long been exploited for use in tortoiseshell jewelry. Tortoiseshell objects have been found in the graves of the Nubian rulers of predynastic Egypt, the ruins of China’s Han Empire, and the middens of pre-Columbian cultures in the Caribbean. Though international trade of tortoiseshell is prohibited today, illegal trafficking continues, and is a primary threat to the conservation status of hawksbill turtles. Learn more about hawksbill sea turtles.

© Dawn Witherington

Olive ridley turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea)

Olive ridleys are the most abundant sea turtle species and yet also one of the smallest, second only to the closely related Kemp’s ridley. They are also widespread, and are found nesting on every continent and many islands across the globe. But don’t mistake the olive ridley’s wide range for ordinariness! These unique animals are also responsible for one of nature's greatest spectacles, called an arribada, Spanish for ‘arrival,’ during which thousands of olive ridleys come ashore simultaneously to nest. It is still a mystery as to how or why the turtles synchronize, though it’s hypothesized that the mass nesting overwhelms predators and allows more baby turtles to make it to the ocean. Olive ridleys are increasingly threatened by trawling and coastal development throughout their range. Learn more about olive ridley sea turtles.

© Dawn Witherington

Kemp’s ridley turtle (Lepidochelys kempii)

The Kemp’s ridley is the smallest of the sea turtles and has a restricted range, nesting only along the Caribbean shores of northern Mexico and in Texas, U.S.A. These diminutive sea turtles are a compelling example that conservation efforts can succeed, even in dire situations. Just fifty years ago, the Kemp’s ridley nearly went extinct. Thanks to dedicated nesting beach protection, a reintroduction program, and the development and implementation of Turtle Excluder Devices in U.S. and Mexican fisheries, the species has rebounded significantly. However, the coast isn’t clear just yet, as Kemp’s ridley populations are still just a fraction of their former size. Learn more about Kemp's ridley sea turtles.

© Dawn Witherington

Flatback turtle (Natator depressus)

The only endemic sea turtle species, flatback turtles nest solely along the northern coast of Australia and inhabit the continental shelf between Australia, southern Indonesia, and Papua New Guinea. Until the late 1980s, the flatback was thought to be a subspecies of the green turtle. Now we know that flatbacks are in fact one of the most unique hardshell sea turtle species, sporting distinct features like a flattened carapace with winged edges made up of thinner, more delicate scutes. Learn more about flatbacks.

The seventh sea turtle species is the sole member of the unique family Dermochelyidae:

Leatherback turtle (Dermochelys coriacea)

The leatherback turtle’s branch on the evolutionary tree split from the other species of turtles about 100 million years ago. They have since evolved a variety of unique characteristics that set them apart, including a soft, flexible shell that is covered in a layer of leathery skin, a lack of scales, the ability to regulate their body temperatures, and their enormous size. The largest of the sea turtles, leatherbacks can reach more than 1.8 meters (6 feet) in length and weigh more than 640 kg (1,410 lbs). During their spectacularly long migrations, leatherbacks regularly dive to depths greater than 1,000 meters (3,281 feet) in search of gelatinous zooplankton (aka jellyfish) to eat. Leatherbacks are rapidly declining in some areas of the world as a result of fishing, habitat loss and degradation, egg consumption, and pollution. Learn more about leatherback turtles.

© Dawn Witherington

Sea Turtle Life Cycle

The life cycle of sea turtles is extraordinary, beginning on sandy beaches as embryos inside of golf ball sized eggs and growing to be as big as 6 feet in length (1.8 m) and more than 1,400 lbs (640 kilograms) in the case of the leatherback.

The following section summarizes the sea turtle life cycle. For a better look, be sure to check out our interactive diagram and detailed description of the sea turtle life cycle.

Adult turtles

Male and female sea turtles will make migrations, sometimes thousands of miles, from their feeding habitats to their natal beaches, usually close to or on the beach from which they hatched. Upon arrival, turtles will congregate in coastal waters and mate with multiple partners.

After a few weeks of mating, female turtles emerge onto the nesting beaches to lay between 50 and 150 eggs, a process that they will usually repeat between 3 and 7 times during the season at intervals of 1-2 weeks, though the exact number of times depends on the species, population, and individual turtle.

Female turtles will mate with multiple male turtles, storing the sperm of all the males that will be used to fertilize their eggs. This means one nest could have sea turtle hatchlings of multiple fathers. © Tui De Roy / Roving Tortoise

Male turtles, once they have mated with as many females as they can and are unable to find any more mates, return to their feeding grounds, leaving the females to continue laying their final clutches of eggs.

The migration back to the feeding grounds can take months, and female turtles, especially, must replenish all of the energy they expended while nesting and migrating. They will spend up to three years feeding and restocking their fat and energy reserves before they return to nest again.

Hatchling turtles

Sea turtle eggs incubate in the nest chamber beneath the sand for 6 to 8 weeks. Sea turtles do not tend to their nests or eggs; eggs are left to incubate on their own in the sand. Once the embryos fully develop, the baby sea turtles will break through their eggshells and, as a group, dig their way up to the surface. This process can take a few days.

The hatchlings usually fully emerge from the nest en masse at night when they can better avoid detection by predators, and crawl rapidly to the sea. Once they make it to the water, the hatchlings enter a multi-day “frenzy state” in which they swim constantly to deeper offshore waters using the energy left over from their yolk.

Most sea turtle hatchlings won’t even make it past the nearshore waters since the greatest density of predators lurk on the beach and in the shallows. © Time+Tide Foundation

After the frenzy state wears off, hatchlings float passively with ocean currents that take them to open-ocean habitats where they will live amid flotsam such as sargassum seaweed mats, driftwood, and other debris (increasingly including ocean plastic pollution). During this stage, which can last anywhere between a few years and decades, the small turtles will have an omnivorous diet.

Once they have grown large enough to better avoid predators, juvenile turtles will join adult turtles in food-dense coastal waters. After they have reached full maturity, which can take a few years to decades, the adult turtles will make their first migration to their breeding/nesting areas.

Sea turtles must grow up on their own, without any parental care. They are guided entirely by their instincts.

Distribution and Habitat

Sea turtles nest on beaches in over 120 countries and are found throughout the world’s oceans, inhabiting waters as far north as Greenland and as far south as the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. While all sea turtles are migratory, the extent of their migrations differs by species and population. For example, leatherback turtles sometimes migrate across full ocean basins, covering as much as 13,000 miles between their nesting and feeding grounds. On the other end of the spectrum, flatback turtles make only small migrations, rarely leaving the Australian continental shelf. Explore data on sea turtle distribution in our interactive online map of sea turtle nesting and migrations.

Leatherback Distribution and Habitat

Leatherbacks are considered the widest ranging sea turtle species, because they regularly cross entire ocean basins to feed or nest and have logged the longest migration of any sea turtle. They are unique from other species for their ability to inhabit waters as cold as 7.5º C (45.5 ºF), for example off of Canada and Greenland. At the same time, they nest on beaches in the tropics and subtropics like most other sea turtles. Gabon (West Africa) and Trinidad (Caribbean) are home to the largest populations of nesting leatherbacks today.

Green Turtle Distribution and Habitat

Green turtles are a widely distributed and highly migratory species that nests on every continent besides Antarctica and, excluding the Arctic, can be found in every ocean basin as well as in the Mediterranean and Red Seas. They generally stick to waters above 20º C (68º F) and seek calm seagrass beds for their feeding grounds. Here you can see a global map of green turtle nesting and in-water distribution.

Loggerhead Distribution and Habitat

Loggerheads are a global species that achieve thousand-mile, transatlantic migrations. Maps on global loggerhead nesting beaches and global loggerhead telemetry demonstrate that they tend to nest in tropical and subtropical regions and often inhabit waters in more temperate regions between nesting seasons.

Hawksbill Distribution and Habitat

Hawksbill turtles are globally distributed and their range, both nesting and migratory, is highly tropical. While hawksbills can be found in all of the ocean basins excluding the Arctic, they tend to make only short, coastal migrations between their nesting beaches and their coral reef foraging grounds.

Olive Ridley Distribution and Habitat

Olive ridleys nest on tropical beaches around the world and migrate into the waters of temperate regions. They are considered the most abundant sea turtles in the world and they come ashore simultaneously by the hundreds and thousands to nest in events called “arribadas”, which means “arrival” in Spanish.

Kemp’s Ridley Distribution and Habitat

Kemp’s ridleys have the most restricted geographic range of all sea turtle species. They nest exclusively in Rancho Nuevo, Tamaulipas, Mexico, and in Texas in the U.S. Their non-nesting range extends between the Northwest Atlantic Ocean, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean.

Flatback Distribution and Habitat

Flatbacks are the least studied of the sea turtles, but we do know that flatbacks spend their entire lives on the continental shelf north of Australia and nest only on the northern coast of Australia.

Taxonomy and Evolution

The seven sea turtle species that grace our oceans belong to a unique evolutionary lineage that dates back at least 110 million years. Sea turtles fall into two main subgroups: the unique family Dermochelyidae, which consists of a single species, the leatherback, and the family Cheloniidae, which comprises six species of hard-shelled sea turtles.

This is the widely accepted phylogenetic tree and evolution of all seven sea turtle species. Turtle illustrations by © Dawn Witherington

Sea Turtle Genetics

Recent advancements in genetic tools have allowed scientists to delve deeper into the evolution of sea turtles and have provided the ability to differentiate among genetically distinct sea turtle groups, called Management Units (MUs), at increasingly finer scales. For example, a recent article identified 26 loggerhead MUs, 76 MUs for green turtles, 26 MUs for leatherbacks, 30 hawksbill MUs, 17 olive ridley MUs, 9 Kemp’s ridley MUs, and 7 MUs for flatbacks. Identification of these distinct genetic populations helps focus and prioritize conservation efforts on the unique and specific threats that each population faces throughout its range.

Ecology of Sea Turtles

The ecological importance of sea turtles is undeniable. Sea turtles are found in habitats from sandy beaches and shallow coastlines to the abyss, and they range in their oceanic movements from the tropics to polar waters. Sea turtles are a food source for marine, terrestrial, and airborne predators and even for some people. They are major consumers of sea life, and their lifestyles and waste products make them ecosystem engineers through their effects on coral reefs, seagrass pastures, sea bottom habitats, and possibly oceanographic forces. Their reproductive routines make sea turtles a dynamic link between land and sea, resulting in the transfer of vast amounts of energy and matter from the oceans to the nesting beaches that affect the ecology of terrestrial consumers from raccoons to soil microbes.

Hawksbill turtles eat sponges that grow on coral reefs, fulfilling an important ecological role that helps reefs to thrive. © Jason Washington / Ocean Image Bank

Sea turtles are important for healthy ecosystems

There are many ways that sea turtles are known to contribute to healthy ocean ecosystems (and likely many ways that are still unknown!). Some of the ways sea turtles are important to healthy ecosystems include:

Green turtles are one of the most important marine megaherbivores and, through grazing, maintain balanced, healthy seagrass beds.

Hawksbill turtles are among very few species that consume marine sponges. They use their sharp beaks to scrape sponges from coral and rocky reefs. In so doing, they help keep sponge populations in check, allowing other reef species to thrive.

Sea turtle nests provide nutrients such as carbon and nitrogen to sandy beaches that benefit coastal fauna and flora and increase productivity throughout the food web.

Sea turtle predators

There are many predators of sea turtles that range throughout their life cycle. Even before hatching from the nest, sea turtle eggs are in danger of being dug up and predated by raccoons, foxes, dogs, wild pigs, crabs, and countless forms of microbes, insects, mites, and more. As hatchlings, sea turtles experience extreme predation both during their brief time on land as they make their way to the ocean, as well as once they enter the water. Once emerging from the nest, hatchlings must avoid birds like vultures, hawks, frigatebirds, and herons, as well as crabs, raccoons, dogs, and more. Once in the water, baby turtles are in danger of being eaten from both above, by birds, and below, by fish and sharks. It is estimated that only 1 in 1,000 eggs will produce an adult sea turtle.

Once a turtle meets adulthood, it has few natural predators. In the water, a turtle may face large sharks and, depending on the location of the nesting beach, nesting female turtles sometimes fall prey to Jaguars.

Sea turtle diet

Sea turtles’ diets vary greatly by species.

During all life stages, leatherback turtles subsist entirely on gelatinous zooplankton, namely jellies and jelly-like organisms and as adults often dive to depths of up to 1,000 meters to pursue their prey.

Green turtles most commonly graze on seagrass, which is what gives their fat the greenish tint for which they’re named. Thanks to their constant grazing, they are considered one of the most important marine megaherbivores and maintain balanced, healthy seagrass beds. Depending on the population and their foraging habitats, green turtles will also eat seaweeds, jellyfish, and algae.

Seagrass, the main diet for green sea turtles, is an important food source and habitat for countless other species, which means sea turtles play an important ecological role in seagrass ecosystems. © Jordan Robins / Ocean Image Bank

Hawksbill turtles in most areas feed primarily on sponges that grow on reefs, a unique and rare diet considering sponges' numerous defense mechanisms, including toxic chemicals, indigestible spongin fibers, and siliceous (glass) spicules. Hawksbills are one of the only predators able to defy sponges’ defense mechanisms, making them a key actor in maintaining reef balance and health. Hawksbills will also feed on marine algae, seagrasses, and mangrove fruits.

During all life stages, olive ridleys, Kemp’s ridleys, loggerheads, and flatbacks eat mostly benthic invertebrates such as crabs, other crustaceans, and mollusks and will also occasionally eat jellies.

Sea Turtle Physiology

Diving physiology

Sea turtles’ flat, elongated shells and long, paddle-like flippers make them extremely hydrodynamic and highly effective swimmers and divers. In fact, turtles are some of the longest and deepest diving marine vertebrates, spending significantly more time beneath the water than at the surface. Leatherbacks, which are the deepest diving of the turtle species, routinely reach depths beyond 1,000 meters (3,280 feet) and have registered dives of up to five hours long. The deepest recorded dive by a leatherback was 4,409 feet (1,344 meters).

The ability to dive so deep and for such extended periods is largely thanks to sea turtles' unique oxygen management and storage adaptations. For example, sea turtle lungs are extremely large, which means that each breath they take provides a large volume of oxygen to use during shorter dives. During longer dives, turtles use oxygen that is stored in the hemoglobin found in their red blood cells and the myoglobin of their muscles. Sea turtles have unusually high levels of myoglobin and red blood cell counts, meaning that there is more oxygen available to sustain them during longer dives.

Turtles also have slower baseline metabolisms than warm-blooded animals, meaning that they require less oxygen for their normal body functions. In addition, they can further reduce their heart rates in preparation for long dives, thereby reducing the oxygen they use while diving.

In addition, sea turtles can withstand the extreme pressure they experience at depth because their shells have flexible connective tissue that allows them to compress slightly under pressure. Leatherbacks have even more unique physiology, detailed below.

In some places it’s said that sea turtles cry when they lay eggs, saddened that they will never see their babies again. While the turtles do, in fact, shed tears, those tears actually serve to excrete salt and keep the turtles’ salinity balanced.

Osmoregulation

Living in the ocean poses a variety of challenges to sea turtles, one of which is maintaining homeostasis in an environment that is three times saltier than their internal fluids. To maintain their internal salinity levels when consuming saltwater and salty food sources, they must constantly excrete excess salt. They achieve this thanks to specialized lachrymal salt glands located behind the eyes that secrete a sodium chloride solution.

Thermoregulation

In terms of temperature regulation, sea turtles are living oxymorons: thermoregulating ectotherms. Ectotherms are animals whose body temperature is the same as or similar to their surrounding environments, and they do not expend energy on maintaining a stable internal temperature. On the other hand, thermoregulating animals do maintain their body temperature regardless of the external temperatures.

While turtles do not have the same thermoregulating system as true endotherms, they can, to some extent, maintain their body temperature thanks to a few key adaptations.

One such adaptation is their large body size. Larger animals have a smaller surface area to volume ratio, meaning that they lose body heat from their skin at a slower rate than smaller animals. Turtles also have lots of adipose tissue, or brown fat insulating the core of their bodies, which allows them to retain a large amount of body heat.

Leatherback turtles, for example, are the largest species of turtle and also have the greatest amount of fatty tissue, which allows them to thermoregulate very effectively and thus occupy very cold water.

Navigation

Sea turtles are incredible navigators that can migrate thousands of miles from their feeding grounds and still find the same beach where they hatched, an ability that until recently was a mystery. However, scientists now know that a turtle’s incredible navigation capability is largely due to an internal magnetic compass that senses the sun and the Earth’s magnetic fields. Each location has a signature magnetic “address” and a turtle imprints the address of the beach where they hatch so they can find it when they return, even decades later.

Scientists have learned about how sea turtles navigate by using satellite telemetry devices like the one mounted on this loggerhead turtle. © New York Marine Rescue Center (NYMRC)

Temperature-dependent sex determination

The sex of a sea turtle is determined during the egg incubation process by the temperature of the sand. Warmer temperatures during incubation will produce more females and cooler sand temperatures will produce more males. More precisely, a nest that incubates at 27.7ºC or lower will produce male turtles and at 31ºC or higher will produce all females. Between these temperatures, both male and female turtles will hatch from the nest.

As temperatures increase due to climate change, researchers in some areas note that nests are producing higher proportions of female hatchlings, a conservation concern as populations become more and more skewed. For example, Raine Island, an important nesting beach for green turtles, is producing 90% female hatchlings.

The unique physiology of leatherback turtles

Evolutionarily, leatherbacks diverged from the other six species of sea turtles about 100 million years ago, which means they have developed a variety of unique characteristics that set them apart. For example, they are the largest sea turtle species, they have a soft, flexible shell that is covered in a layer of leathery skin, and they do not have scales.

A leatherback's homeothermic ability to regulate and maintain its internal body temperature independent of the external temperature sets it apart from other ectothermic reptiles. This ability is possible due to a combination of very unique adaptations. Their dark coloring attracts heat from the sun, which they can retain thanks to a thick adipose, or fat, layer and their large body size, which retains heat better than smaller animals that have a higher surface area-to-volume ratio. In addition, leatherbacks have a specialized blood circulation mechanism called countercurrent heat exchange in which warm blood is directed toward the extremities, warming the colder blood returning to the heart. All of these unique characteristics enable leatherbacks to inhabit colder waters than the other species of turtles.

Leatherbacks have many unique adaptations that set them apart from the other six sea turtle species. One of which is their flexible, skin-covered shell. © Philip Hamilton / CIFAMAC

In addition to a wider longitudinal range, leatherbacks are also able to dive deeper than any other sea turtles, regularly reaching depths beyond 1,000 meters. The evolutionary traits that make such depths accessible to leatherbacks include: large oxygen stores in their muscles and blood; a slowed heart rate that consumes less oxygen; collapsible lungs that prevent decompression sickness; and, a flexible shell that contracts under high pressure.

Threats to Sea Turtles

Sea turtles are built to last. Equipped with unique body armor to protect them from their natural enemies, they have swum the seas since dinosaurs roamed the land. However, in recent history, rapidly increasing human populations have resulted in new and acute pressures, making sea turtle survival ever more difficult. Expert members of the IUCN-SSC Marine Turtle Specialist Group have identified five major threats to sea turtles worldwide: fisheries bycatch, coastal development, pollution and pathogens, direct take, and climate change.

Fisheries Bycatch

It’s estimated that the fishing industry contributes to the death of thousands to tens of thousands of sea turtles each year. Turtles that become trapped in longlines, gill nets, and trawls are discarded as bycatch. Sometimes nets break loose or are cast off as trash and become “ghost nets” that continue to float around the ocean catching turtles and other sea life. And turtles that manage to avoid fishing nets may be impacted by the disruption to their food supply and habitat.

Recent research and conservation efforts have focused on developing solutions to bycatch for sea turtles. This has included such efforts as developing better pound nets, creating and implementing Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDs), illuminated nets that deter turtles, and many others.

Fisheries bycatch is considered to be the biggest threat to sea turtles. Sea turtles, as well as many other marine animals, become entangled in nets and lines both when in use and after they are lost or discarded and left to drift the oceans. © Toby Matthews / Ocean Image Bank

Coastal Development

Every year, sea turtle habitats are destroyed because of shrinking coastlines. Wherever there is boat vessel traffic, whenever a new hotel or high-rise is built up along the shore and the coastline becomes more illuminated, and wherever there is seafloor dredging and beach erosion, sea turtle food supplies and nesting areas can be impacted.

Pollution and Pathogens

Ocean pollution can harm sea turtles in many ways. Plastic pollution, inorganic pollutants, discarded fishing gear, petroleum by-products, chemical runoff, and other forms of pollution can injure sea turtles through ingestion or entanglement. Ocean pollution can also weaken turtles’ immune systems and disrupt nesting behavior and hatchling orientation. Learn more about sea turtles and plastic pollution.

Direct Take / Illegal Trade

Throughout the world, turtles are killed and traded on the global market as exotic food, oil, leather, and jewelry. Over the past 100 years, millions of hawksbill turtles alone have been killed just for the price of their shells. And even though today the global trade of luxury and craft items has reduced thanks to conservation efforts, it remains an ongoing threat to turtles in parts of Africa, Asia, and the Americas.

Climate Change

We are just now learning the extent to which climate change impacts sea turtles. Climate change can impact the natural sex ratios of hatchlings, cause sea levels to rise and erode nesting beaches, increase the likelihood of disease outbreaks, and can escalate the frequency of extreme weather events that destroy nesting beaches and coral reefs. We are also seeing both nesting ranges and migration patterns shifting, likely in response to changes in sand and sea temperatures.

Thanks to researchers and conservationists around the world, we are collecting vital information about sea turtles and ho best to help them. © Brian Hutchinson

Sea Turtles’ Conservation Status

All seven species of sea turtles are listed on the IUCN Red List of Endangered Species, and five of the seven are considered to be threatened with extinction globally. Their Red List statuses are:

Leatherbacks: Vulnerable

Green turtles: Least Concern

Loggerheads: Vulnerable

Hawksbills: Critically Endangered

Olive ridleys: Vulnerable

Kemp’s ridleys: Critically Endangered

Flatbacks: Data Deficient

Because each sea turtle subpopulation, or Regional Management Unit (RMU), experiences distinct threats throughout their distinct ranges, the IUCN-SSC Marine Turtle Specialist Group (MTSG) began evaluating the extinction risk of sea turtle populations in addition to the species’ globally. This method provides more detailed and actionable information about sea turtles’ conservation and facilitated the identification of the most threatened sea turtle populations, the healthiest sea turtle populations, and sea turtle conservation priorities overall.

Addressing all of the threats to turtles is vital but a majority of sea turtle conservation initiatives focus on protecting nesting sea turtles and their beaches, which in some cases has proven successful. However, it is widely recognized that addressing fisheries bycatch and the increasingly problematic issues related to climate change is key to reversing sea turtle population declines long term.

How You Can Help Sea Turtles

Where do you call home? Is it near a beach? The heart of a city? The peak of a mountain? Wherever it is, sea turtles and the threats they face are closer than you might think.

We live in a world of interconnectedness; the threats that endanger sea turtles and other marine species—fishery impacts, coastal development, poaching, pollution, and global warming—result from human behaviors that we all have the power to change. There are a variety of simple actions that you can take in your everyday life that will help turtles:

Choose sustainable seafood options to minimize fishery impacts. For U.S. residents, Seafood Watch provides helpful resources to identify sustainable seafood specific to your location.

Take stock of your consumption of single-use plastics and household chemicals and look for environmentally sound alternatives to help fight plastic pollution.

To decrease your contribution to climate change consider reducing the electricity used in your home, changing the way you get around, and making sustainable food choices such as reducing meat consumption.

To reduce the effect of coastal development, when vacationing on a sea turtle nesting beach, confirm that your accommodations have taken steps to ensure the safety of nesting and hatching sea turtles. If you live near a sea turtle nesting beach, follow best practices to reduce light pollution and minimize other disturbances to nesting and hatching turtles.

Help reduce direct take and the illegal trade of sea turtles by learning to recognize and avoid tortoiseshell jewelry, made from critically endangered hawksbill turtle shells.

The Cultural Significance of Sea Turtles

Sea turtles have held immense cultural significance in various human communities since the early days of humanity, as evidenced by the depictions of sea turtles that have been found in cave paintings throughout the Americas, Australia, Oceania, and Southeast Asia, as well as the current popularity of sea turtle photography, iconography, and even bumper stickers.

Seri elder Alfredo Lopez examines ancient cave paintings—including illustrations of turtles—found near Loreto, Baja California Sur, Mexico. The paintings were likely created by Seri ancestors more than 750 years ago. © Ocean Revolution

The cultural value of sea turtles has been especially significant in coastal communities and indigenous societies worldwide, and sea turtles have been revered by many cultures for centuries, serving as symbols of longevity, wisdom, and resilience. In some cultures, sea turtles are believed to be the earthly manifestations of spiritual beings, and their presence is associated with divine connections and protection. For example, in some Indigenous American cultures, the leatherback sea turtle is considered a symbol of creation and is often featured in origin myths. Similarly, in Hindu mythology, the turtle is associated with Lord Vishnu and the churning of the cosmic ocean, symbolizing the cycle of creation, preservation, and destruction.

In addition to their spiritual symbolism, sea turtles have practical cultural significance as well. Sea turtles have been, and in some cases still are, an important source of food in coastal communities. Sea turtles were also the basis for an extensive global trade in tortoiseshell, which persists to a lesser extent today. Traditionally, many sea turtle hunts were closely managed and integrated into larger cultural practices (weddings, coming of age, taboos, etc.). Opposing views between local communities and conservationists can lead to conflict, and sea turtle conservation is in the process of reckoning with issues such as colonial conservation and parachute science.

In addition, sea turtles’ role in maintaining healthy ecosystems, such as seagrass beds and coral reefs, has an impact on the livelihoods of coastal communities. And in recent decades, sea turtles have also been central to the development of sustainable ecotourism and conservation efforts in many areas. The conservation of sea turtles has become a cultural imperative in many societies, which recognize the immeasurable value of healthy sea turtle populations.

Learn more about the cultural significance of sea turtles in the following articles:

Sea Turtle Facts and FAQs

Sea turtles are remarkable animals. Even after many thousands of years of human-sea turtle coexistence and more than 60 years of modern sea turtle research, there are many things that we still do not know about sea turtles. In this section, we’ll explore some of the many amazing facts about sea turtles and explore some frequently asked questions (FAQs) about sea turtles.

How many sea turtles are there?

It is surprisingly difficult to estimate the number of sea turtles in the world with any reasonable accuracy. This is primarily because they spend almost their entire lives in the sea, while we reside on land. To make defensible estimates of the total number of sea turtles in the ocean, scientists must therefore rely on counting egg-laying adult female turtles and their offspring, combined with math, modeling, assumptions, and a lot of creativity. A recent exercise to estimate how many sea turtles there are in the world produced the following estimates:

Can sea turtles hear?

Sea turtles are capable of hearing, but they appear sensitive only to low-frequency sounds commonly found in near-shore waters (such as the sounds of ocean waves breaking on beaches). It has been suggested, though not proven, that adult turtles use these sounds to help them locate nesting beaches once they have entered the vicinity. The possibility that turtles can detect infrasound (sound too low for humans to hear) has also not yet been investigated. Check out this article for more information on how turtles sense their environment.

How do sea turtles navigate?

Sea turtles have at least one major sensory ability that humans lack: the ability to perceive Earth’s magnetic field. The magnetic sense of sea turtles appears to be remarkably sophisticated, allowing them to obtain both directional and positional information. Turtles can perceive the direction of the magnetic field much as a compass does and can thus distinguish between north and south, as one example. In addition, they can detect subtle variations in Earth’s magnetic field, and they use this ability in long-distance navigation. The magnetic field is a particularly useful source of navigational information in the ocean, because it is present at all depths, remains constant during day and night, and does not vary with weather or season. Learn more about how sea turtles navigate.

How long do sea turtles live?

Because we only see female turtles every few years when they nest, combined with the fact that it’s very difficult to determine an accurate age of an individual turtle, it’s extremely complicated to determine how long sea turtles live.

Therefore, most longevity estimates have been conducted on captive sea turtles and suggest that turtles live between 30 and 80 years depending on the species. Learn more about how long sea turtles live.

What are the most endangered sea turtles?

Of the seven sea turtle species, Kemp’s ridleys and hawksbills are listed as critically endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, making them the most endangered sea turtle species. However, species-level classifications for sea turtles don’t always paint an accurate picture, as some populations within a species may be increasing whereas others may be extremely threatened.

Therefore, the IUCN Marine Turtle Specialist Group has taken a finer-scale approach and evaluated the status of sea turtle populations. In 2012, the group named the 11 most threatened populations of sea turtles in the world:

East Atlantic Hawksbills

East Pacific Hawksbills

Northeast Indian Ocean Hawksbills

West Pacific Hawksbills

East Pacific Leatherbacks

Northeast Atlantic Loggerheads

Northeast Indian Ocean Loggerheads

North Pacific Loggerheads

Northeast Indian Ocean Olive ridleys

West Indian Ocean Olive ridleys

How many eggs does it take to make an adult sea turtle?

While the answer depends on the population of sea turtles in question, mathematical estimates based on years of data collection and nesting beach monitoring indicate that 1 in 1,000 eggs will result in an adult sea turtle. Read more about how this number was calculated here.

Researchers can tell the success of a sea turtle nest, or the proportion of eggs that hatched, by digging up the egg shells after the baby turtles have emerged. This data is important for calculating survival estimates. © University of South Pacific

How can I tell a male sea turtle from a female sea turtle?

In adult turtles, determining the sex of an individual turtle is relatively easy – a male has a long tail that extends well beyond the carapace whereas a female has a short tail. With hatchlings and sub-adult turtles, it’s not possible to determine their sex simply by looking at them; they are not sexually dimorphic, meaning that they do not have any external features to distinguish males from females.

When hatchlings are developing inside their eggs, the temperature of the nest will determine the sex of the hatchlings – warmer temperatures trigger the embryo to develop ovaries (female) and cooler temperatures trigger gonads (male). The procedure to detect these sex organs is not possible on live hatchlings, but new methods can tell the sex of a hatchling with a small amount of blood. Learn more about how to tell if a sea turtle is male or female.

As adults, male sea turtles have long tails, like this loggerhead turtle in Belize. However, sub-adult turtles (which in some cases is the first 30 years of their life) have no external features that can be used to reliably determine their sex. © Ben Hamilton

Where do baby sea turtles go when they leave the beach?

Very little is known about sea turtles’ lives from the time they depart their nesting beaches as hatchlings until they return to shallower coastal waters years later as larger “teenage” turtles. In fact, so little was historically known about this period in sea turtles’ lives that it has been dubbed the “lost years.”

Today, newer, smaller satellite tags are becoming available that allow researchers to track younger turtles for longer distances. As more turtles are tagged in more regions and more oceans, we are finding that we can’t assume that baby turtles in different areas are behaving in the same way.

The answer to where baby sea turtles go depends on where in the world the question is asked. What we do know is: (a) that little sea turtles are surface-dwelling oceanic creatures that actively orient and actively swim and (b) that we have a long way to go until we fully understand the sea turtle's lost years.

Still have a sea turtle question?

Let us know if we missed something!

More Reading & Resources

We’ve tried to cover every possible topic in this guide to sea turtles, but we have only scratched the surface of available information about each one. We’ve linked out to high-quality sources of additional information throughout the guide and we encourage you to click those and explore them in greater depth. In addition, here are a few resources for more learning about sea turtles:

Sea Turtle Species - An overview of the seven sea turtle species, with detailed information, photos, facts, and maps for each species.

Sea Turtle Life Cycle - A detailed look at the life cycle of sea turtles with an illustrated life cycle diagram.

Threats to Sea Turtles - Learn about the threats that endanger sea turtles.

Sea Turtles and Plastic Pollution - An educational video and guide to the impacts of plastic on sea turtles

How You Can Help Save Sea Turtles - Learn about ways that you can help save sea turtles every day.

Articles from The State of the World’s Sea Turtles Reports - Dozens of free articles written annually by global experts in sea turtle biology and conservation since 2006.

The State of the World’s Sea Turtles (SWOT) Report - Our free annual magazine with up-to-date articles, maps, and information about sea turtle biology and conservation.

Interactive Online Sea Turtle Map and Database - Our comprehensive interactive map of sea turtle nesting, satellite tracking, genetics, and more, featuring data contributed by hundreds of partners worldwide.

Static Maps of Sea Turtle Nesting, Migrations, Distribution, and More - View and download maps of sea turtle biogeography that have been created for and published in past volumes of SWOT Report.

Directory of Sea Turtle Research and Conservation Projects - Discover sea turtle research and conservation programs worldwide, find sea turtle volunteer opportunities, sea turtle tourism programs and more as you explore The Sea Turtle Directory, our global interactive map of sea turtle research and conservation projects.